What place should works of art have in churches, and does it make any difference whether they are beautiful or not?

Date added: 11/07/2016

1 comments/replies so far. Read the discussion. Join in. >> (You need to log in first.)

What place should works of art have in churches, and does it make any difference whether they are beautiful or not?

Introduction

Art and religion have a chequered history; inextricably linked but often seen to be representing opposing thought-worlds. The scars of iconoclasm still loom large on the ecclesial body and opinions differ vastly on what is and what is not appropriate in a place of worship. The power of images, especially religious images remains strong. Freedberg notes that;

People are sexually aroused by pictures and sculptures; they mutilate them, kiss them, cry before them and go on journeys to them; they are calmed by them, stirred by them, and incited to revolt. They give thanks by means of them, expect to be elevated by them, and are moved to the highest levels of empathy and fear. They have always responded in these ways; they still do.[1]

But is this question of appropriateness based solely on moral grounds, or also aesthetical ones? Is art more acceptable in places of worship if it is beautiful? In order to answer that, one must unpack the word ‘beautiful’; the concept of beauty has been interpreted widely across the centuries, some of which will be looked at in this essay to help answer the question of the place of art.

I will look briefly at the role of art in a Christian context, as well as a short look at the role of icons in Orthodox traditions. Having identified some possible roles of art in churches, I will touch upon some of the arguments against having art in places of worship before moving onto the larger question of ‘what makes art beautiful?’ and whether that is necessary, or even important for artwork in churches.

The role of art in places of worship

Art has been used in places of worship for centuries, both as decoration and as a tool for instruction. In cultures and contexts where the majority of the congregation did not have direct access to Biblical texts (either through lack of translation or illiteracy), art was used as a means of illustrating Biblical messages or teachings. Art used in church in this way breaks down boundaries of literacy – one does not need special training or education to understand its message. Its place continues to be legitimized by its active role in living the Christian message of evangelising. Graham Howes notes that as early as 1005 it had been proclaimed that “art teaches the unsettled what they cannot learn from books”[2] but Gregory the Great, who lived in the 6th century, is attributed with the idea even earlier, with it being claimed he said “what writing does for the literate, a picture does for the illiterate.”[3] Arguably, this pedagogical tradition has not died out: Sunday schools regularly use artistic activities to help explain Christian teaching or traditions to children.

The role of art in the fabric of churches can also be understood as a witness to worship. As a physical manifestation of belief, church buildings are often beautifully and intricately decorated beyond practicalities or necessities. Such decoration signifies the distinct and special role of the building as a place of worship. It marks it out and dedicates the building to God. Working on and creating such decoration is an active form of worship; upholding and supporting such buildings subsequently is a continuation of this worship. The act of creating something beautiful with the intention of pleasing God enables a relationship with the divine by establishing a connection between the artist and God. This relational aspect of art to worship is crucial, not just for the artist themselves in mimicking the creative role of the divine, but also for those who participate in art as viewers. The exuberance of decoration in, or as a part of, churches is a physical manifestation of the joy felt by worshippers at their relationship with the divine and a way of marking that relationship. For, Luther, this relational aspect brought some issues, however; Beth Williamson notes that “Luther saw a danger in religious art; he became opposed to the endowment of artworks with the intention of earning merit with God.”[4]

A third role of visual art in worship is as an encouragement or focus to worship. Art in this role is not trying to teach or impart knowledge. It is meditative, a focus for contemplation of the divine. Such art can be soothing or provocative, can lull the viewer into an acknowledgement of the divine or shock them into it. This variety of relationships means the style and type of art can also be varied, as it aims to speak emotively. Howes quotes Bonaventure who saw visual art:

Not only as an open scripture made visible through painting, for those who were uneducated and could not read, but also as an aid to the ‘sluggishness of the affections…for our emotion is aroused more by what is seen than by what is heard.[5]

Beyond art to action

We have highlighted some of the ways art is used in Western traditions but in Eastern Orthodox traditions, the role of art is much more vital. Alan Ogden writes;

The Tradition of the Church is expressed not only through words, not only through the actions and gestures used in worship, but also through art - through the line and colour of the Holy icon.[6]

But can icons be truly described as art in the same way as other paintings? They are physically created in the same way, by transferring paint to wood, or paper, but they are very different in their finished form. They are painted prayerfully – the artist, or icon writer’s intention is critical to creating an icon – and this prayerful creation enables an icon with power. They are seen not merely as static objects but as cognisant depictions, with knowledge and awareness, which can have real and direct influence on one’s life. Icons are revelatory, they have more autonomy, there is a two-way process of creation between the icon and the painter. Howes comments on the vitality and activity of icons saying, “The icon is not a picture to be looked at, but a window through which the unseen world looks onto ours.”[7] This does not exclude the artistic input of the artist but this is no longer the sole input. Ogden comments:

Because the icon is a part of a Tradition, icon painters are not free to adapt or innovate as they please; for their work must reflect, not their own aesthetic sentiments, but the mind of the Church.[8]

Graham Howes goes further, saying “an icon painter’s execution is not an assertion of his own individuality, but a magical act.[9]

Icons clearly have a distinctive role and place within the Eastern Church; they are a functioning part of the belief system. Their place as pieces of art is guaranteed in churches by virtue of their active role in the life of the church. But do they have to be beautiful? Arguably the most important element is that they are prayerfully rather than beautifully created. However, they will typically feature rich colours and lots of gold to mark their high status and the esteem they are held in, worthy of worship. Because of the long tradition of icon writing, icons are immediately recognisable and individual artistic merit is almost homogenised or made irrelevant. Ogden notes that:

It is important icon painters are good artists, but it is even more important that they should be sincere Christians, living within the spirit of the Tradition, preparing themselves for their work by means of Confession and Holy Communion.[10]

So if an icon is truly created, with the will of the artist being that they are reflecting and enriching the beliefs of the church, would it matter if such a work was not beautiful? Or would it always be beautiful because of those very intentions? Rowan Williams, when reflecting on the work of Maritain, remarks that:

If it is well and honestly made, it will 'tend' towards beauty – presumably because it will be transparent to what is always present in the real, that is the overflow of presence which generates joy.[11]

Looking at icons in this understanding, they will always be deemed beautiful because icon writers put aside personal creative desires to create truly and honestly.

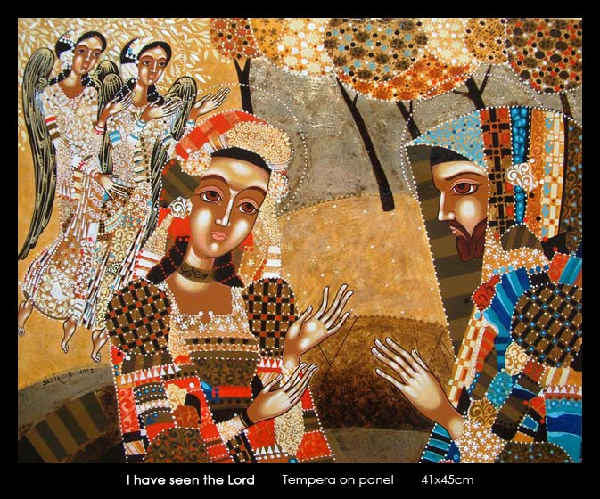

Modern icon writers, such as Silva Dimitrova, use the same techniques for paintings in an iconographic style which are not icons. They have been described by Richard Leachman, who outlines their spiritual but not strictly religious nature:

Her pictures embrace joyously colourful patterns, magical symbolism and deep serenity. They articulate a world of inner light and love, of a poetically mystical life that is both of nature and of humanity. [12]

In Dimitrova’s case, many of these paintings show Biblical scenes or figures; an Easter scene, or a resurrection scene. Some are not Biblical, showing musicians or circle of life motifs. These paintings appear more contemporary than her icons but are clearly of the same style. In Dimitrova’s ‘I have seen the Lord’, she is depicting a typical Noli me tangere, a subject matter wholly appropriate for use in worship. And yet, style and content are not enough to guarantee beauty – as Maritain notes, the artist must intend to produce something true. Even then, the art produced may not be appropriate for or have a place in church.

What is beauty?

If, based on what we've discussed, we accept that art has a place in churches, we must now question whether that art must be beautiful. This goes beyond what it looks like on a superficial level: there are greater questions about what constitutes beauty. We have looked at Maritain’s ideas around truthfulness and beauty but truthfulness, and therefore beauty, can be interpreted in many ways and expressed in even more. When thinking of a church context, which interpretations are appropriate?

While it is challenging, possibly blasphemous, to depict the divine, artists can reflect one element of it by depicting what they see in nature, the outcome of a creating God. Leonardo da Vinci held nature up as the ultimate model, saying “Painting…compels the mind of the painter to transform itself into the mind of nature itself and to translate between nature and art.”[13] This emphasis on nature was especially prevalent during the late 1800’s and particularly associated with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (seen in paintings such as Holman Hunt’s ‘The Scapegoat’ with its fantastically vivid mountain and desert background) and subsequently with the art critic John Ruskin. Ruskin had an overtly religious element to his artistic judgements. He was often critical of artists for their failures to highlight the majesty of creation through nature. He commented of landscape artists that:

That which ought to have been a witness to the omnipotence of God, has become an exhibition of the dexterity of man; and that which should have lifted our thoughts to the throne of the Deity, has encumbered them with the inventions of his creatures.[14]

This is the same thought we have come across from Maritain and in Eastern Orthodox icon writing: for art to have true integrity, the artist must put aside personal concerns and desires to the extent that the work has independence separate from the artist, for as Maritain says “it is beautiful when it is released from the artist.”[15] When the focus is on the artistic skill of the artist instead then naturalistic works of art lose their worship element. For Ruskin, this goes even further – he sees such art as “the painter’s taking upon him to modify God’s works at his pleasure, casting the shadow of himself on all he sees.”[16] So to paraphrase Ruskin, where paintings echo the glory of creation, they are perfectly appropriate in places of worship but if they go beyond and claim the glory of the painting as their own then they are not.

The flip side of this naturalistic art is more apophatic, seeking to display the ‘otherness’ of the divine through the absence of known elements. This can be seen in paintings with other-worldly backdrops, such as Leonardo’s ’The Virgin of the Rocks’ – the background is not recognisable, with outrageous rock formations, water bodies and unknown plant species. By separating the figures and the unknown landscape from the known earth, Leonardo makes a comment on their otherness, their unknowability. This then emphasises a particular element of beauty of the divine, one which is entirely appropriate for use in places of worship, that of non-humanity. Emphasising this otherness can be appealing in places of worship as it emphasises the comforting elements of divinity such as omnipotence and the fact that the divine has power, grace and potential far beyond humanity.

However, this otherness can be interpreted in other ways, as with paintings of the sublime. Nietzsche sees art as a duality of Apolline and Dionysiac forces which “exist in a stage of perpetual conflict interrupted only occasionally by periods of reconciliation.”[17]This encompasses both the joyfulness epitomised by Apollo but also the horror of the Dionysian and artists, for Nietzsche, can combine both at once.[18] Nietzsche looks to Greek theatre where he finds “From highest joy there comes a cry of horror or a yearning lament at some irredeemable loss.”[19] This horror is driven by the human fear of ultimate death[20] and this is why paintings of the sublime seek to impose a sense of this human frailty on the viewer. This results in paintings which provoke feelings of fear or danger and are still beautiful in essence because of their depictions of grandeur and awe-inspiring majesty in nature. And yet a painting such as Frederick Watts and his assistant’s ‘Chaos’, despite its beauty and naturalistic subject, would not be appropriate for a place of worship due to its sense of desolation. Similarly, Philip James De Loutherbourg’s ‘An Avalanche in the Alps’, with its human futility in the face of nature. These do not reveal truths about a divine presence, whether apophatically or not, but rather suggest the absence of a benevolent divine. Whilst there may be divinity present in the stupendous landscapes or power of nature, often sublime images pit natural forces against human ones, ably highlighting human frailty but doing little to support a Christological view of a harmonious creation.

We have already looked at the benefits of ‘truthful’ renditions of Biblical stories in art and their didactic functions. They can be teaching tools both literally and morally and as direct depictions of Biblical stories have solid Christological foundations. But as we have seen, truthfulness does not always equate appropriateness, whether due to disturbing content or artistic comment. Banksy is renowned for subverting traditional styles, (as in Madonna and Jesus Da Bomb) which arguably have been created to speak a truth felt by the artist to comment on the role and work of the contemporary church and yet would not be suitable in a place of worship. These works question the very fundamental elements of Christianity, which while valuable, is not the primary focus of places of worship. Although places of worship have a responsibility to push worshippers to explore their beliefs, this is done within the safety of a belief system; if that were removed there is a danger of pushing believers beyond the boundaries of their faith. Truthfulness is also open to interpretation too – as Pilate so famously asked – ‘What is truth?’[21] The artistic truth Maritain envisages is described by Chaim Potok in his novel ‘My name is Asher Lev’, a story about a gifted Jewish artist: “You can do anything you want to do. What is rare is this actual wanting to do a specific thing: wanting it so much that you are practically blind to all other things, that nothing else will satisfy you.”[22] This eloquently describes the all-encompassing nature of this artistic truth and highlights its rarity. It blinkers the artist to conventions and societies’ expectations when they are focused on creating truth. But this truthfulness does not mean that the art they create is appropriate for use in place of worship. The exception to this may be in depictions of the passion and crucifixion, which is a subject from which places of worship cannot shrink, but must face. But this may be because, unlike such violent stories as the massacre of the innocents or the beheading of John the Baptists, there is a clear and jubilant counter to the crucifixion in the resurrection story. It could be argued that this is the key feature that makes works of art appropriate for places of worship, whether or not they enhance or advance established Christian ‘truths’ rather than Biblical or artistic ones.

Is beauty comfortable?

We have touched upon the idea of ‘truthfulness’ in the creation of beauty and the role of the artist’s intent but the setting and the people are also important. Hughes describes the role of John Hussey in encouraging his parish to accept modern (somewhat controversial) works of art by Graham Sutherland and Henry Moore: it was not plain sailing for Hussey but he wrote that he was convinced that even if his congregation originally found ‘“something not exactly what they would have chosen” or which they “could not quite understand”, I do not think would matter, because they would be willing, with encouragement, I feel sure to accept it and wait for its beauty to grow on them.” Hussey’s role was vital, along with that of the congregation, when deciding the role and appropriateness of art in churches.

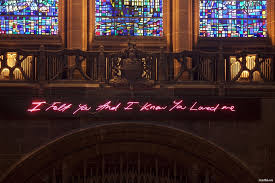

Many of these problems are connected to the subjectivity of more contemporary art – we have already noted the work of Banksy, used to comment on Christianity and religion in the contemporary world. Another controversial figure, who purposefully entered into the world of religious art, is Tracey Emin. Emin was commissioned by Liverpool Cathedral in 2008 to create a piece of work, an unusual choice given that the artist is not overly connected with religion or faith. The finished piece of work is in Emin’s distinctive pink neon handwriting and reads “I Felt You And I Knew You Loved Me.” On it’s website, Liverpool Cathedral explains it’s long-standing relationship with art, saying;

Artists were often commissioned to produce work which would teach, inspire, challenge and even intimidate the faithful, illustrating to them the beliefs of the Church and the practices required of the followers of Jesus Christ…this tradition continues today, and Liverpool Cathedral is no exception, in spite of being a cathedral of the modern age.[23]

This points to the tradition art shares with Christianity and the religious motivation behind the commissions; Emin is famously an artist who personally invests a lot in her works. Yet this commission was not universally accepted. A contemporary newspaper article about the work commented that “Some assume the message is ‘salacious’ because it comes from Emin.”[24] It is true that the message could be interpreted in a physical or sexual manner – after all to ‘know’ someone in a Biblical sense is to have sex with them – but it is not restricted to that. At a spiritual level, this statement is an amazing affirmation of the power and grace of divine love for humanity. Emin herself does not tie down the meaning of the work, saying;

All my neons are very open-ended. Unlike a lot of my artwork where I force it on you, it’s up to you how you interpret this. It depends how you want to be touched by something.[25]

Her intentions for creating the artwork are similarly ambiguous; she says of her inspiration, “I thought it would be nice for people to sit in the cathedral and have a moment to contemplate the feelings of love.”[26] This could again be interpreted as a religious desire or an erotic one. Despite these ambiguities, however, this is a piece which is still appropriate for use in a place of worship – it provokes and encourages deeper evaluation of Christian truths looking at the nature of our relationship with the divine. In it, Emin is the recipient of someone else instigating a touch, just as we are recipients of divine grace and love. By using this experience, at a base level, of a relationship with another human and imbuing it with such poignancy and raw emotion strips bare the fragility of human nature and our desire for relationship – whether with each other or with the divine.

This notion of art illustrating humanity’s relationship with the divine may also help explain why some uncomfortable art retains its beauty – graphic or realistic depictions of the crucifixion for example, or emotive depictions of mater dolorosas or depositions. Artists have a duty to render these as realistic and churches have a duty to utilise them. This is not only because they should not be sugar-coated as stories in themselves but also because through these depictions people are able to relate to places of worship even in the most difficult of circumstances. Hughes quotes Hussey, who in turn quotes Feibusch, who fights against simplistic or idealistic Christian art saying;

The men who came home from the war, and all the rest of us, have seen too much horror and evil; when we close our eyes terrible sights haunt us; the world is seething with bestiality; and it is all man’s doing. Only the most profound, tragic, moving, Sublime vision can redeem us. The voice of the Church should be heard above the thunderstorm and the artist should be her mouthpiece.[27]

Clearly context is vital here – Hussey was commissioning Sutherland to create a crucifixion scene in the aftermath of the Second World War and its accompanying horrors. The resulting picture is full of suffering and is deeply emotive. And yet surely this is how crucifixions should be depicted in an attempt to convey not only the physical suffering of Christ the man but get beyond even that to somehow depict the agony of Christ the divine. Upon completion of the Sutherland, Hussey’s Church Council were shown it to see whether they accepted it or not. One member is recorded as commenting curtly “This is one of the most disturbing and shocking pictures that I have seen; therefore I think it should go into the church.”[28] This attitude of not shying away from the truths expressed in art is vital to let us properly evaluate its role in church.

Issues raised by art in places of worship

This suitability debate is one that has been ongoing for centuries within the Church. During the 16th century iconoclastic movement, much art and decoration in churches was destroyed. Arguments were made that the art itself was being worshipped, rather than being used as a conduit to worship God, or was a distraction to proper worship. This is clearly a difficult distinction to draw, especially when the art is perceived as particularly beautiful, and therefore more likely to inspire admiration or even reverence. The content of some religious artwork can also be drawn into question, despite being Biblical. Nudity, gratuitous violence and sex are all frequently depicted in religious art works. And yet arguably none of these themes are conducive to Christian worship. Depictions of Christ or the saints in various stages of undress are common and yet are a very real opportunity for temptation. Barolsky paraphrases Vasari, who describes the influence felt by Fra Bartolommeo’s Saint Sebastian, painted for a Florentine church but painted entirely nude. The painting was so stirring that it aroused impure thoughts in the women who worshipped there, and upon their confessing their sins, the painting was removed.[29] This, as Barolsky point out, “reaffirms the problem of the ambiguity between a religious image’s spiritual meaning and its carnal illusion.”

We have touched on Maritain’s belief that an artist’s intention has an impact on the outcome of the work. It can be argued that this works in reverse. When you look at the striking similarities between an artist’s devotional and secular work, it is surprising how much cross-over there is. Pieces such as Correggio’s ‘The Magdalene’, compared with his Venus from ‘Venus, Mercury and Cupid’, or Leonardo da Vinci’s ‘St John the Baptist’ compared with his ‘Bacchus’ for example. This could seem to suggest that rather than creating religious images for devotion, artists merely appropriated those saints or Biblical stories most suitable to themes they were already pursuing, such as the sensuality of the naked form. In this way they legitimise their work as Christian.

While there are taboo subjects such as violence or nudity depicted in religious artworks it is fairly rare to see depictions of incest, fratricide or rape, yet these are also all Biblical. So it is clear that it was not enough for subject matter to be Biblical: it must also be appropriate. While we have already seen that it is not enough for religious art to follow traditional styles it is also not enough for it to blindly follow Biblical themes without regard for what those are. This is the same issue surrounding ‘truth’ we have already looked at – it is not enough for a work of art to depict a ‘truth’ if that truth is damaging in a worship environment. This decision, of what is or is not appropriate in a worship environment, is arguably not the decision of the artist but will have an effect on what artists decide to depict – if only because artists like selling paintings!

Conclusion

Through attempting to answer the question of the role and appropriateness of art in places of worship we have come up with some broad conditions for their use; those of the truthfulness of the art, of the intention and selflessness of the artist, the importance of Biblical or Christian messages or themes and the sensitivity towards the suitability of the church for the art work.

So, art does clearly have a role in church. From the unique role of icons in the eastern tradition to modern contemporary art installations in cathedrals up and down the country, the role of art in churches is as varied as the art itself. We have touched upon some of the ways in which art can be helpful to viewers, by going beyond words and offering some glimmer of the divine which cannot otherwise be understood, the numinous in creation. It can teach, inspire, unite and it crosses boundaries of race, language, gender. Part of this may be that, generally, religious art attempts to speak of mysteries of the relationship religion creates between the divine and humanity. Chaim Potok describes this universality in his novel, saying; “Every great artist is a man who has freed himself from his family, his nation, his race. Every man who has shown the world the way to beauty, to true culture, has been a rebel, a “universal” without patriotism, without home, who has found his people everywhere.”[30] This is mirrored through depictions of the example we have in the story of the incarnation and human life of Christ. The relationships shown through Christ’s life are a reassurance that we as humans can have these sorts of relationship with the divine.

But we have also seen that art, even (or maybe especially) religious art, can also be dangerous. On a lesser level, it can actually detract from worship of God by setting up the artist and artwork as worthy of worship, rather than leading through the art to the divine. This then leads towards the dangers of idolatry and is not only of danger to the artist but also viewers. We have also looked at some of the dangers of accepting artworks on the basis of their biblical or religious foundations rather than their effect or message. Some biblical messages or stories do not necessarily have a place in places of worship, whether due to their violent or graphic nature, or because they speak of a truth without quantification – such as the frailty of human nature without the reassurance of the divine love.

Part of the responsibility of the appropriateness of art in places of worship is down to the commissioner or curator – whether this is the priest or not, they hold a responsibility to be sensitive to the needs and resilience of the worshippers who will be in that place. But they have a responsibility to not only be sensitive to the dangers of pushing too far but also of not pushing far enough. It is the responsibility of the church at large to go beyond the comforts of religious art to the edges where deeper, sometimes uncomfortable truths lie.

But do these works of art have to be beautiful? As we have seen, definitions of beauty are not absolute but fluid, conditional and sometimes contradictory. There is no one easy definition of what beauty is, especially when combined with questions of religion and belief and so there is no definitive answer for whether works of art should be beautiful. Each person will bring their own subjective background to a work of art, with their own associations and histories. What could be argued as a ground rule for works of art in places of worship is that they should attempt to speak of a truth and provoke a reaction – it doesn’t matter what the reaction is as long as the art stirs the emotions and has an effect. And that should be the ambition of works of art in churches; to provoke the viewer to feel a reaction to a divine truth and through that, even if unknowingly, to enter into a relationship with that divinity.

Georgie Morgan is the Executive Assistant to the Mission Theologian in the Anglican Communion and studying for a Masters in Christianity and the Arts at King's College, London.

Pictures referenced

-

I have seen the Lord – Silvia Dimitrova

-

The Scapegoat – Holman Hunt

-

The Virgin of the Rocks – Leonardo da Vinci

-

Chaos – George Frederick Watts and Assistants

-

An Avalanche in the Alps - Philip James De Loutherbourg

-

Madonna and Jesus da Bomb – Banksy

-

I felt you and I knew you loved me – Tracey Emin

-

Crucifixion – Graham Sutherland

-

The Magdalene – Antonio da Correggio

![Corregio Magdalene]](../../g_lib_articles/148.png)

-

Venus, Mercury and Cupid – Antonio da Correggio

-

John the Baptist – Leonardo da Vinci

-

Bacchus – Leonardo da Vinci

Bibliography

-

Apostolos-Cappadona, Diane, (ed.), Art, Creativity and the Sacred, (New York: The Continuum International Publishing Group Inc., 2005)

-

Baxandall, Michael, Painting and Experience in Fifteenth-Century Italy, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1972)

-

Barolsky P., The Mysterious Meaning of Leonardo’s “Saint John the Baptist”, Notes in the History of Art

-

Vol. 8, No. 3 (Spring 1989)

-

Brent Plate, S., Blasphemy: Art that Offends, (London: Black Dog Publishing, 2006)

-

Campbell, Graham, Renaissance Art & Architecture, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004)

-

Howes, Graham, The Art of the Sacred: An Introduction to the Aesthetics of Art and Belief, (New York: I. B. Tauris & Co. Ltd., 2010)

-

Murray, Linda, The High Renaissance and Mannerism, (London: Thames and Hudson Ltd., 1995)

-

Nietzsche, F. W., ‘The Birth of Tragedy’ In Guess, R., and Speirs, R., (Eds.), The birth of tragedy and other writings, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999)

-

Ogden, A., Revelations of Byzantium, (Oxford: Centre for Romanian Studies, 2002)

-

Potok, Chaim, My name is Asher Lev, (New York: Anchor Books, 1972)

-

Ruskin J., Extracts from Modern Painters, from Modern Painters / v.1: Of General Principles, and of truth, (London: George Shaw, 1906)

-

Williams, Rowan, Grace, Necessity and Imagination: Catholic Philosophy and the Twentieth Century Artist, Lecture 1: Modernism and the Scholastic Revival, 2005

-

Williams, Rowan, Grace, Necessity and Imagination: Catholic Philosophy and the Twentieth Century Artist, Lecture 4: God and the Artist, 2005

-

Williamson, Beth, Christian Art: A Very Short Introduction, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004)

Websites referenced

Silvia Dimitrova’s website - http://www.silviadimitrova.co.uk/

Liverpool Echo - http://www.liverpoolecho.co.uk/

Bible used

NRSV

[2] Howes, G., The Art of the Sacred: An Introduction to the Aesthetics of Art and Belief, (New York: I. B. Tauris & Co. Ltd., 2010), pg 12

[3] Williamson, B., Christian Art: A Very Short Introduction, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), pg 66

[11] http://rowanwilliams.archbishopofcanterbury.org/articles.php/2104/grace-necessity-and-imagination-catholic-philosophy-and-the-twentieth-century-artist-lecture-1- as of 29/05/16

[13] Baxandall, M., Painting and Experience in Fifteenth-Century Italy, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1972), pg 119

[14] Ruskin J., Extracts from Modern Painters, from Modern Painters / v.1: Of General Principles, and of truth, (London: George Shaw, 1906), pg 133

[15] http://rowanwilliams.archbishopofcanterbury.org/articles.php/2108/grace-necessity-and-imagination-catholic-philosophy-and-the-twentieth-century-artist-lecture-4-god-a as of 29/05/16

[17] Nietzsche, F. W., ‘The Birth of Tragedy’ In Guess, R., and Speirs, R., (Eds.), The birth of tragedy and other writings, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), pg14

[24] http://www.liverpoolecho.co.uk/news/liverpool-news/message-love-liverpool-tracey-emin-3473408 as of 15/04/16

[25] http://www.liverpoolecho.co.uk/news/liverpool-news/message-love-liverpool-tracey-emin-3473408 as of 15/04/16

[26] http://www.liverpoolecho.co.uk/news/liverpool-news/message-love-liverpool-tracey-emin-3473408 as of 15/04/16

[29] Barolsky P., The Mysterious Meaning of Leonardo’s “Saint John the Baptist”, Notes in the History of Art

Vol. 8, No. 3 (Spring 1989), pg 14

Articles by Georgina Morgan

What place should works of art have in churches, and does it make any difference whether they are beautiful or not? (11/07/2016)